In the previous blog we examined what would constitute a mature market and took some time examining the German PRS as this is often held up as one that is mature and that operates well.

Affordability and the cost of housing is becoming an increasingly emotive issue. The narrative that all landlords are wealthy, exploitative and are benefitting unfairly from the transfer of resources from one social group to another ie from tenants to landlords is one that is increasingly being played out in the press and latched onto by pressure groups and politicians alike. The origins of rent controls in the UK and other locations have their genesis in such views with controls being portrayed as a panacea for the all the perceived inequity of the current system. Most reasonable people from all stakeholders accept that things can certainly be improved in the Private Rented Sector (PRS) but we do not believe that the ongoing demonisation of landlords is fair. It is in fact is far from the reality of the situation and is not helpful in promoting sensible and engaged debate to seek solutions and may actually cause more problems as landlords decide to leave the sector.

Now let’s investigate what elements of maturity we can see in the Scottish PRS.

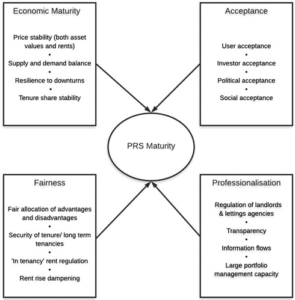

So, what criteria would identify a mature and sustainable PRS? In a recent study by Farhad Farnhood and Colin Jones list the following:

Economic maturity, Acceptance, Fairness and Professionalisation

PRS Market Maturity Framework

Source Farnhood and Jones

Economic maturity in a PRS market is characterised by stable rents and asset values that result on a lower risk profile and ensure ongoing viability. This is directly linked to an equilibrium being reached between supply and demand. So, this could mean an element of rent control or stabilisation being bought into the PRS. The result can be an economically mature PRS market is more likely to be resilient and its tenure share is likely to be relatively stable.

In terms of acceptance a mature PRS would not be stigmatised, it would be accepted by all stakeholders so mainly tenants and landlords but also investors, wider society, the press and policy makers. In Scotland there appears to be a high level of satisfaction amongst renters with 84% of households in the PRS being very or fairly satisfied with their housing (Scottish household survey 2019). This would point that part of the criterion of tenant acceptance at least seeming to be met in Scotland. That said the ongoing anti landlord rhetoric and negative portrayal of landlords in the press and by pressure groups like Generation Rent show that social acceptance has some way yet to go.

Examining mature PRS’s in Europe would suggest that fairness is another criterion that would suggest a market has reached maturity. Risks associated with operating within a market need to be spread between stakeholders in a balanced fashion with security of tenure a feature in European sectors that might be considered mature. Risk to tenants in terms of affordability would be unfair rent rises, so as we have seen already an element of rent control can been seen as part of a mature sector.

Historically Britain, like many other countries, controlled both the initial rent that landlords could charge and any subsequent increases. Rent control was introduced during the First World War and the tightening of the regime after 1939 meant that landlords were unable to make an economic return; this was a key factor in the dramatic shrinkage of the sector. A series of post-war revisions to the regulations were intended to bring permitted rents more into line with market prices. As mentioned in the previous blog, the rules were finally swept away entirely by the 1988 Housing Act. In Scotland there have been moves towards legislating for some form of rent control but so far this has not been introduced in practice.

At this point it is perhaps worth taking brief look at rent control and what this actually means.

The term ‘rent control’ can be used generically to cover a multitude of different policy mechanisms. Most commonly in the economic literature the term “generations” of rent control is used. Mainly this is either “first generation” or “second generation” and sometimes third generation.

The hardest level of control is first generation, this normally means some form of rent freeze and is the one that most people will have in their minds eye when controls are discussed.

“First generation rent control is a nominal rent freeze that leads to a fall in real rents and to a rent level that is significantly below the market rent level”

Hans Lind (Rent Regulation: A Conceptual and Comparative Analysis 2001, p43).

Second generation rent control is different and can cover a multitude of possible interventions and they tend to be somewhat softer in approach. The focus of such controls is to try and moderate the behavioral impacts of regulation by allowing rental adjustments to reflect real life situations such as variable market conditions, cost inflation, or the costs of refurbishment. The result of this is such approaches can rather be viewed as “rent regulation” instead of “rent control”.

This is a complex and wide ranging subject and something we will revisit in more detail in another blog.

Rent regulation is closely tied to security of tenure. In 2016 Shelter carried out a study of “mature” European PRS’s that focused on government intervention to ensure that the needs of landlords and tenants are balanced. In the study Shelter argued that among the sample of 32 European Countries they carried out higher levels of security of tenure for tenants correlated with PRS maturity.

Since 1997, the default form of tenancy in the UK has been the assured short hold tenancy. This generally runs for an initial fixed term (six months or one year), after which it becomes a periodic (month to-month or week-to-week) tenancy. This has changed in Scotland and the introduction of the Private Residential Tenancy (PRT) which gives tenants a significantly higher degree of security of tenure would point towards a maturing market.

Professionalisation is another aspect of mature European PRS’s and is primarily characterised by a higher degree of regulation of those operating in the sector i.e. Landlords, tenants, letting agents. This is certainly in evidence in the Scottish market with the regulation of letting agents with a code of conduct and minimum training levels. Though we would argue that this has created a two-tier system which is inherently unfair as DIY landlords are not required to meet a minimum required standard to let their own properties. This is especially relevant as 62% of people living in the PRS rent direct from a landlord in Scotland.

Rhetoric in the UK has for many years, perhaps even decades, been directed at securing an increase in institutional investment in the private rented sector. This is known as build to rent (BTR). The thinking is that such investors would also increase professionalism and drive down costs because large holdings will produce economies of scale and lower risk; it also may reflect a certain persistence of the view that individual landlords can be rapacious scoundrels and that other countries manage better because institutional investors help stabilise the market. Again, we are seeing increasing levels of institutional investors investing at scale in BTR in Scotland. But it is worth noting that the international evidence shows that in fact it is individual landlords dominate in almost all countries.

So, in summary the PRS is accepted to a degree by users, the government, the wider community and investors but not to a level that would indicate a mature market. The growth of the PRS proved resilient to the Global Financial Crisis, which is a further indicator of maturity, but has been dampened by recent fiscal changes that have reduced the financial attractiveness of landlordism, perhaps a continuing step to filtering out short term speculators.

The Scottish Government is committed to the promotion of the PRS introducing further regulation, and a new form of tenancy (the PRT) giving a greater level of security of tenure and proposed moderation of rent rises. So, in terms of fairness Scotland has rebalanced the risks and disadvantages in the tenant position. These initiatives should improve the social acceptance of the PRS and take Scotland a step closer to the mature market framework seen in many European countries.

From a wider perspective there is a good degree of professionalisation within the operation of the PRS, and recent regulation has improved this further. In addition, there is an abundance of information available to market participants which again points to a maturing market.

However, there are other areas for example the supply and demand imbalance and affordability issues that would suggest there are areas that have not yet reached a state of maturity so perhaps the market is still in a transitional phase.

Looking to rent out your property? Glenham offer a property management service as well as property investment advice. Get in touch to discuss your needs.